The death of creativity and purpose: ChatGPT and the future of work

ChatGPT and LLMs are going to redefine the nature of work, and we are at risk of losing our sense of purpose in the process.

There's something very, very wrong about the way A.I. is going at the moment. And I'm not talking about the threat of it blowing us all up or flooding the world with fake news and images. I'm referring to the massive void it is threatening to create in our very sense of purpose and the lack of serious discussion about the long-term implications of that.

The early indicators are already flashing. If you've heard of ChatGPT - and, more broadly, the explosion of the Large Language Model (LLM) - then you're probably in one of three camps by now. You're either an A.I. enthusiast following the frenzied progress excitedly and trying as many of the new tools as you can; a tech-savvy skeptic who believes the new wave of LLMs are going to be useful tools but the hype is undeserved; or you're sticking your head in the sand about the whole thing and hoping it'll all blow over like crypto.

Regardless of which camp you're in, your awareness of the impact of LLMs will invariably give rise to a sense of dread in some form. If you're an A.I. enthusiast you're probably experiencing some level of FOMO as you struggle to keep up with the pace of progress. If you're a tech-savvy skeptic you're likely prone to episodes of self-persuasion while fears of being replaced stir at the back of your mind. And if you're sticking your head in the sand, well, we all know why that is.

I fall somewhere in between the first two camps. I am an A.I. enthusiast, having worked in the field since 2016. But I am also a tech-savvy skeptic who, having been in the tech scene for several decades now, has seen several major tech revolutions that promised to change everything, only to settle into the general fabric of life and work. Computers, the internet, mobile phones and social media all came, caused a sensation, made a few billionaires, but ultimately did nothing to alter the familiar pattern of going to work five days a week, earning a salary and working until retirement.

People like me have long known that A.I. would eventually consume most of the mundane work that humans currently perform. It has already been happening in a gradual way for several years already. But since the explosion of new generative A.I. models this past year the pace of replacement appears to be accelerating. In the past few days alone IBM announced its intentions to replace up to 30% of its workface with A.I. over the next few years, while Hollywood writers are, at the time of writing, embroiled in an intriguing standoff with studios over the threat of replacement by LLMs like ChatGPT.

While I generally tend to be stoic about the loss of jobs due to A.I. (in my experience the workforce tends to shift over time towards new jobs created by the new technologies), it is precisely the creative nature of the most recent generative A.I. technologies that is worrying me. The very fact that IBM and Hollywood see opportunity for human redundancy from the same technology despite targeting very different human functions - back-office admin versus creative writing - is evidence that we have actually created the first general-purpose artificial intelligence technology with real-world utility. And, by extension, real-world consequences.

To be clear, I am not talking about artificial general intelligence (AGI) here. I personally believe that discussions comparing the intelligence of machines to that of humans is as redundant as comparing a plane to a pigeon. What I am suggesting is that human communication - in the form of writing, speech, art, music and all the other ways in which we connect with each other - is the one thing that has kept us at the top of the intelligence pyramid, and we are about to understand just how fundamental that is to absolutely everything.

The insidious spread of pointlessness

A few months ago I was having a beer with a very good friend of mine. This friend holds a PhD in artificial intelligence from one of the world's most prestigious universities and currently works for a major tech firm on natural language applications. He has been using GPT-3 for a good while now and has built and deployed real-world applications with it. I asked him how work was going, and his face dropped. "It's fine," he said. "I just don't really feel in control any more". My friend is first and foremost an engineer, having plied his trade in software development for most of his career up until his transition to the A.I. field. When pressed on what he meant by not feeling in control, he lamented the fact that LLMs are so unpredictable that he can never feel fully confident in the work he produces. With traditional software engineering, you write some code, you test it, you release it and then you fix bugs as they pop up. There's a rational cadence to it that creates a cycle in which you are frequently challenged, occasionally frustrated, but emotionally rewarded when you overcome obstacles and release something that works. There's always a nagging fear that something will break but as you acquire experience you counter that fear with the security of knowing that you can dive into the code and fix things when required.

Not so with LLMs. The "black box" nature of their trained model architecture means that you can't simply open them up and tweak things when they go awry. You can only adjust your prompts and fine-tune the model with additional data, then hope for the best. That sense of satisfaction born out of identifying and then fixing a specific problem - a core part of the enjoyment of programming as any experienced developer will tell you - is denied. Working with generative A.I. is closer to the experience of training a dog than it is writing software. For a software engineer like my friend, the experience ends up feeling somewhat hollow by comparison.

I have felt the same hollowness in my own interactions with LLMs. In the past few weeks I have tried to produce content with the aid of various different tools including ChatGPT, Jasper.ai and Copy.ai. What I loved about these tools was how quickly they could help me sketch out a structure for an article and help prevent writer's block by auto-suggesting copy based on what I had just written. The first time I committed to writing a full article with A.I. I timed myself and was elated when I discovered it took me a third of the time to write a long-form article compared to my usual turnaround. But then, when I came to publish it, I found myself hesitating to hit the button. I suddenly felt uncertain about the quality of the content, fuelled by a disconnect between myself and the text attributable to the fact I had only originated about 30% of the copy. The rest of it was written by the A.I. and then edited by me. It felt hollow, so much so that I went back and rewrote all of the text produced by the A.I., paraphrasing and rewriting until only the core structure of the article could be credited to the A.I. In the process I had cut the time saving from two thirds to about 15%. From saving an entire day's worth of time to just a couple of hours. But at least it felt like it was mine.

Fortunately, unlike my friend, writing is not the main part of my work. It is a part I enjoy very much though, and that is why it felt hollow to automate that work away. Yet if I was to try and make it as a freelance writer now I would face a monumental challenge from LLMs. In the past week a Reddit user who plies their trade as an author and writer lamented that they had lost all of their content writing contracts in the past few months because of ChatGPT. The particularly telling quote from that thread is this one:

"Some of [the clients] admitted that I am obviously better than chat GPT (sic), but $0 overhead can't be beat and is worth the decrease in quality."

The author goes on to express a sense of pointlessness towards their beloved craft that echoes the hollowness my friend and I experienced:

"As I currently write my next series, I can't help feel silly that in just a couple years (or less!), authoring will be replaced by machines for all but the most famous and well known names."

This sentiment is repeated time and again on sites like Reddit, as similar nihilistic comments have appeared from software engineers, teachers, students, lawyers, music producers, graphic designers, marketers, podcast writers, psychologists, and many more. While many of these comments express the palpable fear of job losses, the more dangerous underlying sentiment is the potential paralysis created by this fear. Because this latest wave of A.I. is so generalised and moving so quickly, there is a real danger of a general sense of hopelessness taking hold amongst knowledge workers who are, for the first time, having to face the harsh truth about automation: it only needs to be "good enough" to replace you.

The Great Narrowing and the end of originality

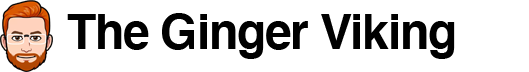

The problem is, this is not a truth that has come out of nowhere. An examination of the creative sector over the past 20 years shows there has been a gradual narrowing of the fields of play in nearly ever corner of it. Consider Hollywood, for example. In 2019 - the last full year of cinema before the pandemic - every single one of the top 10 movies was either a sequel, a remake or part of a franchise. Not a single top 10 film was an original piece of work, and only two films from the entire top 20 list were originals.

Compare that to 1999:

In this year, seven of the top 10 movies were originals, and 14 of the top 20 were. In a 20-year period the number of original movies dropped from 70% to only 10%. Creativity as expressed by originality has been squeezed out in favour of generic, reliable brand names. Meanwhile, top 20 box office revenues rose from $3.1bn in 1999 to $5.9bn. Adjusted for inflation, that's an increase of 25% from roughly the same number of ticket sales (ticket sales volume increased only 6% in that same period). In other words, the Hollywood studios made more money by narrowing their range and focusing on squeezing more out of a smaller number of safe bets. No wonder they're so keen to replace writers with A.I.

A similar pattern exists in music, with a study as long ago as 2012 proving that musical timbre and dynamic variation has flattened out over the years, which in plain English means it's all the same volume and uses the same combinations of notes. Meanwhile, a comparison of the annual top 20 Billboard songs from 1999 versus 2019 again reveals a similar flight to safety within the music industry. Here are the top 20 songs from 1999, with 19 different artists and 3 collaborations:

Compared to 2019, where the number of different artists has dropped to 15 and the number of collaborations has increased to 8 - almost half the list. This is significant as collaborations are a form of hedging in the music industry, where record labels will group popular artists together to expand reach to two or more fanbases, thereby limiting risk:

In a similar vein, the number of artists who appeared in both the 1998 and 1999 Top 20 lists was three, whereas six artists from 2018 appeared in the 2019 Top 20 - double the amount. In both movies and music, the formula for commercial success has been cracked and the number of productions making up the lion's share of revenue is shrinking. Originality is dying out, and the tough truth for creators is that consumers don't seem to care. In fact, quite the opposite. LLMs are simply accelerating a trend that has been building for years - we have just hit the hockey stick part of the exponential curve.

The pattern extends across almost any form of media you can think of. A cursory scroll through any social media feed will yield hundreds of copycat posts and unoriginal content; search for any business topic and you will find hundreds of blog posts with variants of the same headline talking about the same thing; graphic design has become so standardized that there are now multi-million dollar "Design as a Service" platforms like DesignPickle offering unlimited graphic design for only a few hundred dollars a month. The explosion of global interconnectivity facilitated by the internet, social media and creation platforms like blogs and YouTube has generated such a vast amount of content that it has all blended together into one indistinct wave of white noise. Creativity was a commodity before ChatGPT set the world on fire.

When originality is no longer required or even desired, diversity of creators is moot. Generative A.I. feels like the logical outcome of this process. We face a future where all creations come from a single monolithic source, stripped of character and personality, a globulous amalgamation of every human voice blended together into a single nebulous hum.

Love thy robot

But what of our idols?, you may ask. Creative work isn't just about the work itself, we also revere the creators. Van Gogh is synonymously famous with his Starry Night painting. Quentin Tarantino films attract audiences for his name alone. Shakespeare commands respect the world over for his plays. Of course all three of these names produced objectively outstanding work and have earned their reputations, but far fewer people are familiar with Utagawa Hiroshige or Paul Signac, two of Van Gogh's biggest influences and equally as talented, or Samuel Fuller, one of Tarantino's most revered film directors and biggest inspirations, or Christopher Marlowe, Shakespeare's contemporary who many believe Shakespeare actually plagiarised.

For every well-known creator there are thousands of equally gifted others whose work never reaches a mainstream audience. The purpose of celebrity in this context is in some senses a filter for the consumer who clearly does not have the time to digest all of the world's works and is looking for shortcuts to pieces that are worth the time investment. A famous name is basically a seal of quality endorsed by the crowd: a proclamation that this individual is one of the best at what they do and can be trusted to produce work that you will enjoy.

Can this same trust ever be ascribed to an artificial intelligence? The answer to that comes in two parts: firstly, an examination of existing evidence that people can emotionally connect to A.I. and secondly, an inquiry into the need for celebrity in a monocreative generative A.I. world.

In answer to the first question, there is indeed evidence that people are quite willing to connect with, and trust, artificial entities. Replika is an A.I. chatbot whose role is to act as an artificial companion and even lover. The app has over two million users and 250,000 paying subscribers, with multiple accounts of users genuinely falling in love with their digital companions. In a more pertinent example, a Reddit user recently admitted to having trained an A.I. on their ex lover's text messages so that they could talk to their "ex" after the breakup - a chilling echo of a Black Mirror episode. They described the experience as "sad, but it also feels good" - a choice of wording that arguably encapsulates the hollowness that is a theme of these new interactions. Of course it's easy to argue that these people are acting out of loneliness and that's a valid point, until we remember that loneliness is massively on the rise.

Besides, there are plenty of other markers of our willingness to connect with non-human creators. Look no further than Lu do Magalu, a 3D generated "virtual influencer" with over six million followers who behaves just like any other social media influencer, brand sponsorships and everything. Or how about the Korean virtual band Eternity, made up of entirely A.I.-generated members whose songs have amassed millions of views on YouTube:

Admittedly it is only the faces that are A.I. generated, but then again what better symbolism is there of the erasure of human recognition in favour of efficiency? As the CEO behind Eternity admitted in a BBC interview, "the advantage of having virtual artists is that, while K-pop stars often struggle with physical limitations, or even mental distress because they are human beings, virtual artists can be free from these". She went on to say "the scandal created by real human K-pop stars can be entertaining, but it's also a risk to the business". Referring back to the risk aversion trend in Hollywood and pop music discussed in the previous section, it's easy to see how A.I. generated content is irresistibly appealing to the corporate entities who control these industries. It feels almost inevitable that this is where we the market is headed.

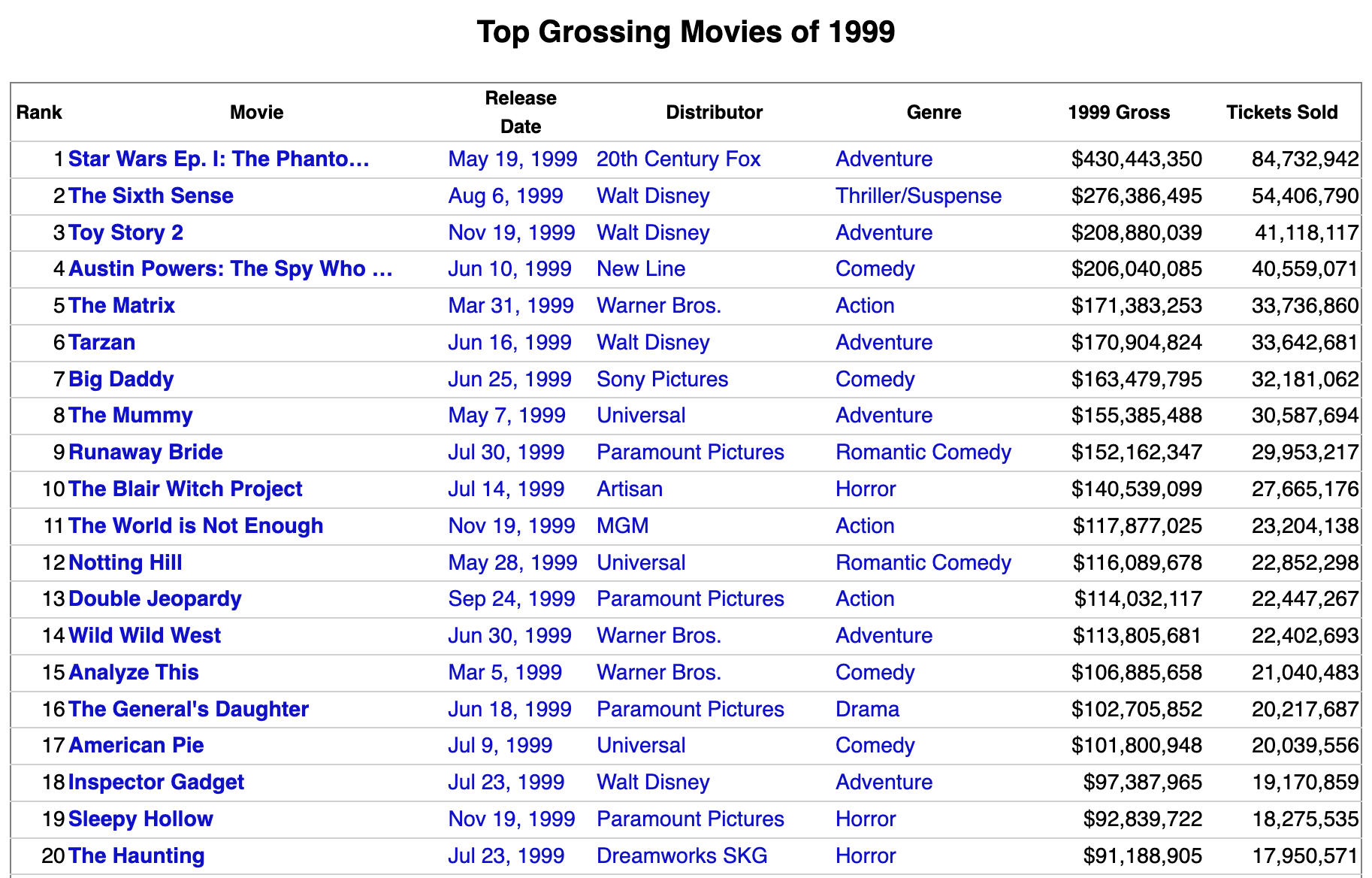

The second part of the question is whether celebrity is even needed in a post-generative-A.I. world, or whether the end product is all that matters. In some senses this question has already been answered by the success of movies like "Avengers: Endgame", whose appeal was far more about the product than the actors, writers or director. But beyond that there is already strong evidence that authors are becoming less relevant, with multiple A.I.-generated products winning awards and acclaim despite not having recognised creators. There are now multiple examples of A.I. generated art winning art and photography contests, while A.I. generated music already has its own version of the Eurovision Song Contest. Meanwhile, the real music industry is witnessing a terminal decline in the sale of albums, indicating a swing towards individual songs most often heard as part of a collection of tracks in a Spotify playlist. Like everything else, just nameless products for consumption, unless you can be bothered to look at who the artist is when a track is playing.

Indeed, the Spotify playlist is a pretty good emblem of the new paradigm that generative A.I. is pushing us towards. The death of the renowned creator and the flood of increasingly generic content creates a large trail of product that now needs some other filter to push through. That filter, inevitably, is us.

Hail to the curator

The Great Narrowing that I referred to in an earlier section in relation to the variety of content could also accurately describe the narrowing of the way in which we choose our content. The unstoppable rise of the recommendation algorithm has underwritten a seismic shift from proactive discovery to reactive browsing, where suggestions are served up to us on a plate for us to sift through at our leisure. This has not only served to devalue individual creations (an alternative is no more than a finger tap away at any given point), but it has also created an environment of consumption that hinges on the idea of curation far more than it ever used to. As we engage with apps like Spotify, Netflix and even Medium, the algorithms pay attention to what we consume and adjust to serve us up more content that we would like. Some people will be more proactive in their curation and meticulously build playlists to match their diverse moods and tastes, but thanks to algorithm-based platforms - another form of A.I., let's not forget - we have gone from a world where most people relied on critics or celebrity to guide their choices to one where individual curation-as-a-service is the norm.

To date that has led to a smaller and smaller handful of creators dominating the lion's share of attention, for reasons I have discussed earlier in this article. But assuming the next logical step is a transition away from human creators to artificial ones, what does that mean for the human creators being replaced? They will need to make a choice at some point in the near future: either adjust their role within their industry to accommodate the new paradigm and keep on earning a living, or give up trying to make money from their craft altogether and accept a much smaller return from their creative output. What generative A.I. means, in reality, is that the chances of becoming a famous musician, actor, author etc will shrink even faster than they have been prior to the LLM-fuelled explosion, while the amount of content against which creators will need to compete will become unfathomable.

What kind of role adjustments will be needed remains to be seen, but logic suggests that a massive shift towards curation is inevitable. If we are about to face an unprecedented deluge of A.I. generated content then somebody will need to curate it. Exactly how that curation will take place is uncertain; it may be a technical process of adjusting algorithms and fine-tuning A.I. models to improve their recommendations to end users, or it could be that we see a rise of celebrity editors whose skills in piecing together A.I. generated outputs become highly valued. Either way, the foundations have already been laid by the proliferation of algorithm-driven content platforms.

In the business world, content writers are inevitably going to be less in demand - as seen by the Reddit user mentioned earlier who lost all his clients to ChatGPT. I can speak from experience to the fact that creating content with A.I. is much more of an exercise in direction and editing than it is in actual writing - curating the A.I.'s suggestions and piecing them together. Graphic design and other crafts are equally under pressure, but the paradigm is the same. Getting the desired output from an image generator like Midjourney is entirely a process of figuring out how to write your brief in the right way for it to execute, choosing the best output and then making adjustments in an image editor if required. The role of the creator is transitioning entirely to that of director, curator and editor.

You pass the butter

As a species we are equipped to achieve extraordinary things. The promise of A.I. was meant to be that it would free us up from mundane work so that we could focus on doing more of those extraordinary things. And yet the feeling I get with this latest wave of generative A.I. and its broad applications across so many fields, both creative and non-creative is that we are being increasingly pushed into a smaller and smaller corner of existence where our value as thinkers, problem-solvers, decision-makers, and creators is being undermined.

Knowledge work makes up a significant percentage of GDP in developed economies, and a rapidly expanding proportion of the developing world's too. If such work is to be reduced to a more mechanical process of curating and editing the output of machine-generated content, what percentage of that knowledge workforce gets left behind?

All this is less of a concern for people like me, who have been working in a field for 20+ years. Frankly the transition to merely editing my business-related content will be a welcome one once I get used to the idea of A.I. being a legitimate creator. But for people starting out in a knowledge career there is already a pervading sense of pointlessness. Posts with titles like "As a student, I am scared for what my future holds" and "I'm a new student and im worried with ChatGPT" are popping up on Reddit, while a survey by the New York Times of high school kids in the US uncovered comments such as the following:

"I personally believe that the use of chatbots and AI in school is dangerous for motivation and knowledge. Why write if a bot does it for me? Why learn when a bot does it better?"

"I think it is a bad thing for schools since students can become underdeveloped in their literacy skills — writing stories or essays — and would give people no incentive to learn and that would lead to them becoming lazy."

"One of my biggest worries is that I would rely too much on these tools and lose the capacity for critical and creative thought."

This last quote is a very valid concern echoed by more experienced workers as well, such as this experienced programmer on Reddit who claimed ChatGPT was "ruining" him as a programmer: "All I'm doing now is using the snippet to make it work for me. I don't even know how it works. It gave me such a bad habit but it's almost a waste of time learning how it works when it wont even be useful for a long time and I'll forget it anyway".

I have experienced this myself, not just with code but much longer ago with GPS technology. When I first learned to drive, in 1997, I became quite good at directions and general orientation, learning to navigate around a complex city like London via specific landmarks and general spatial memory. As GPS started to become a mainstay however, my sense of direction deteriorated so badly that now I struggle to even drive to my sister's place without Google Maps. I don't consider this a major issue as being able to navigate manually isn't a particularly essential requirement in a developed country like the UK. On the rare occasions where I have not been able to rely on Google Maps I have still managed just fine. What I have appreciated is the mental space that has been freed up by not having to think too hard about where I'm going.

In the case of knowledge work, however, thinking about what you're doing is the whole job. If we delegate too much to A.I. systems like ChatGPT then we risk losing the critical functions of creative ideation, decision-making and learning that are part of the process. To refer back to my friend who works in the natural language field, his transition from learning to building to editing A.I. has left him feeling somewhat empty, and his active brain is looking for ways to feed itself. If too many alternative avenues for such mental activity shut down due to A.I.-driven redundancy then a severe existential crisis is all that's left.

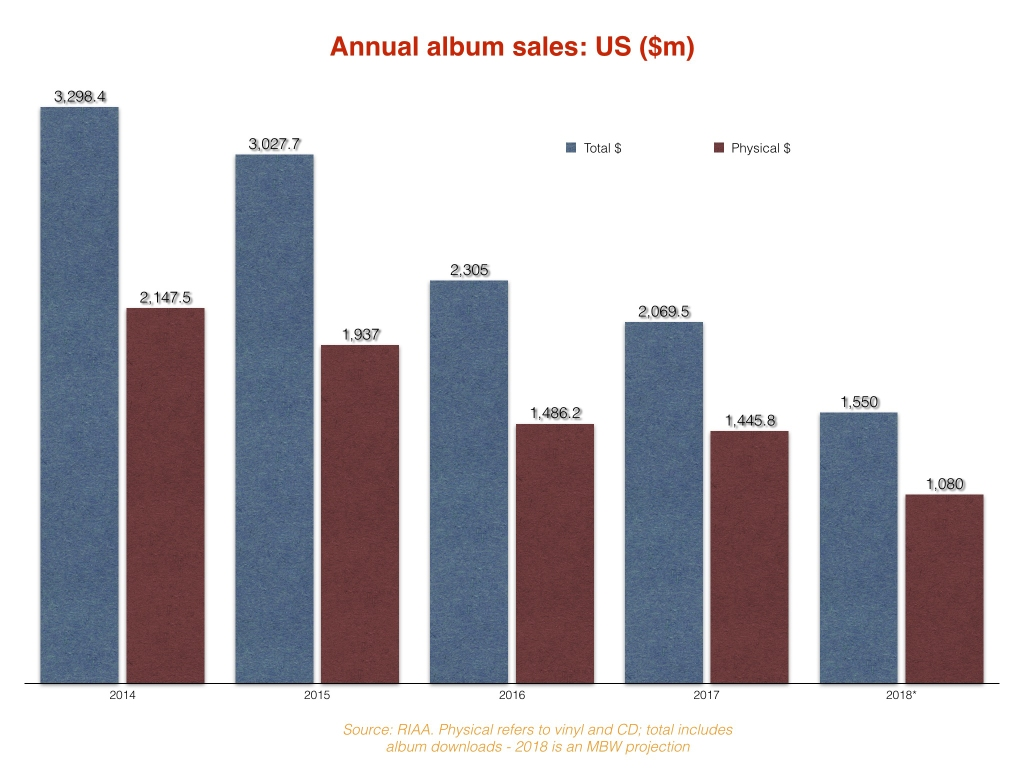

This loss of meaning in the work that will be partly automated by A.I., as opposed to fully usurped, is arguably a more pressing concern as full automation is harder to achieve than part automation, and part-automation is very much part of the initial roadmap for most corporations assessing generative A.I. By way of example, a recent Accenture report provides this illustration of how a customer service job could be broken down into 13 components of which four would be fully automated and five of the remaining nine would be "augmented":

That same report conveniently skirts over the issue of what this person is meant to do with the time freed up, cheerfully declaring that "language tasks account for 62% of the total time employees work, and 65% of that time can be transformed into more productive activity through augmentation and automation" without ever defining what "more productive activity" might be. Without a definitive answer to that question, the cynic in me expects the spare time to be filled with doing the job of someone else who got let go because now the entire customer service role can be performed in half the time. That certainly appears to be IBM's view, as we saw earlier. Of those who are left, expect a brain drain from smart people who no longer feel fulfilled by their semi-automated jobs.

I don't wish to sound like a doomsayer. In truth there is optimism around the future of work in this brave new world. Firstly, like with all breakthrough technologies, there are new jobs being created by A.I. In fact, the 2020 Future of Jobs survey by the World Economic Forum predicted up to 97 million jobs by 2025, although the more recent 2023 survey updates that to suggest that LLMs could also automate up to 50% of tasks, backing up Accenture's analysis that predicts 40%. Nonetheless, new job creation is inevitable and the WEF highlights significant growth in jobs like Data Analyst, Scientist, Machine Learning Specialist and Digital Transformation Specialist. Secondly, the existential threat caused by LLMs has significantly fuelled the dialogue around topics like Universal Basic Income with renowned figures weighing in on the need for a serious examination of this concept in light of how the future of work is going to develop. Leading think-tank the Adam Smith Institute published an article on this subject in the past week, stating that "automation has been transforming the labour market for decades and the development of generative AI is about to kick that into overdrive. We don't even need artificial general intelligence in order for a universal basic income to make sense".

Assuming the financial pressure of needing a job gets relieved by something like UBI (and that's a big if), we can be optimistic about progressing towards a world where we simply don't need to work as much. In which case, writers like our friend from Reddit can spend their spare time enjoying their craft. That is the dream often sold to us. My friend who works in A.I. has found more time and space for additional consulting work which is bringing him not just more income but is also stimulating his mind with different challenges to his daily routine. Perhaps this type of diversified work is where the future really lies for all of us.

Back in 2017 I wrote an article titled "Why Self-Employment is the future of work", in which I predicted that A.I. and automation would lead to an increase in self-employment and a decline in big companies and brands. The advent of LLMs has forced me to alter my thinking slightly on this topic, as it is becoming clear that the big companies and brands are going to use this tech to entrench themselves even further in their domination of the mainstream. Job losses will still force people into self employment, but it is now evident that there is a real risk of there simply not being enough work to go around. The work of curation and editing requires a much smaller pool of people than creation does, and that work is already being automated anyway.

The only logical solution is to embrace the new era that this latest wave of A.I. is bringing in whatever way you can. According to the World Economic Forum's analysis, 85 million jobs will be displaced by 2025 so the sooner you can get a head start the better. Let the age of curation start with your own job today.